Gelijkheid of vrijheid, Thomas More versus Niccolò Machiavelli

Gelijkheid of vrijheid, Thomas More versus Niccolò Machiavelli

Voor de tijdgenoten Thomas More (1478-1535) en Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) waren het falen van de politiek, de sociale wantoestanden en de corruptie in de westerse maatschappijen waarin zij leefden (respectievelijk het Engeland en het Italië van het begin van de 16de eeuw) er de oorzaak van dat zij hun kritiek op de situatie via hun geschriften aan de wereld zijn gaan bekend maken. More deed dat in zijn satirisch werk Utopia (uit 1516) en Machiavelli in enkele politieke werken, waarvan de Heerser (uit 1513) het meest bekende is.

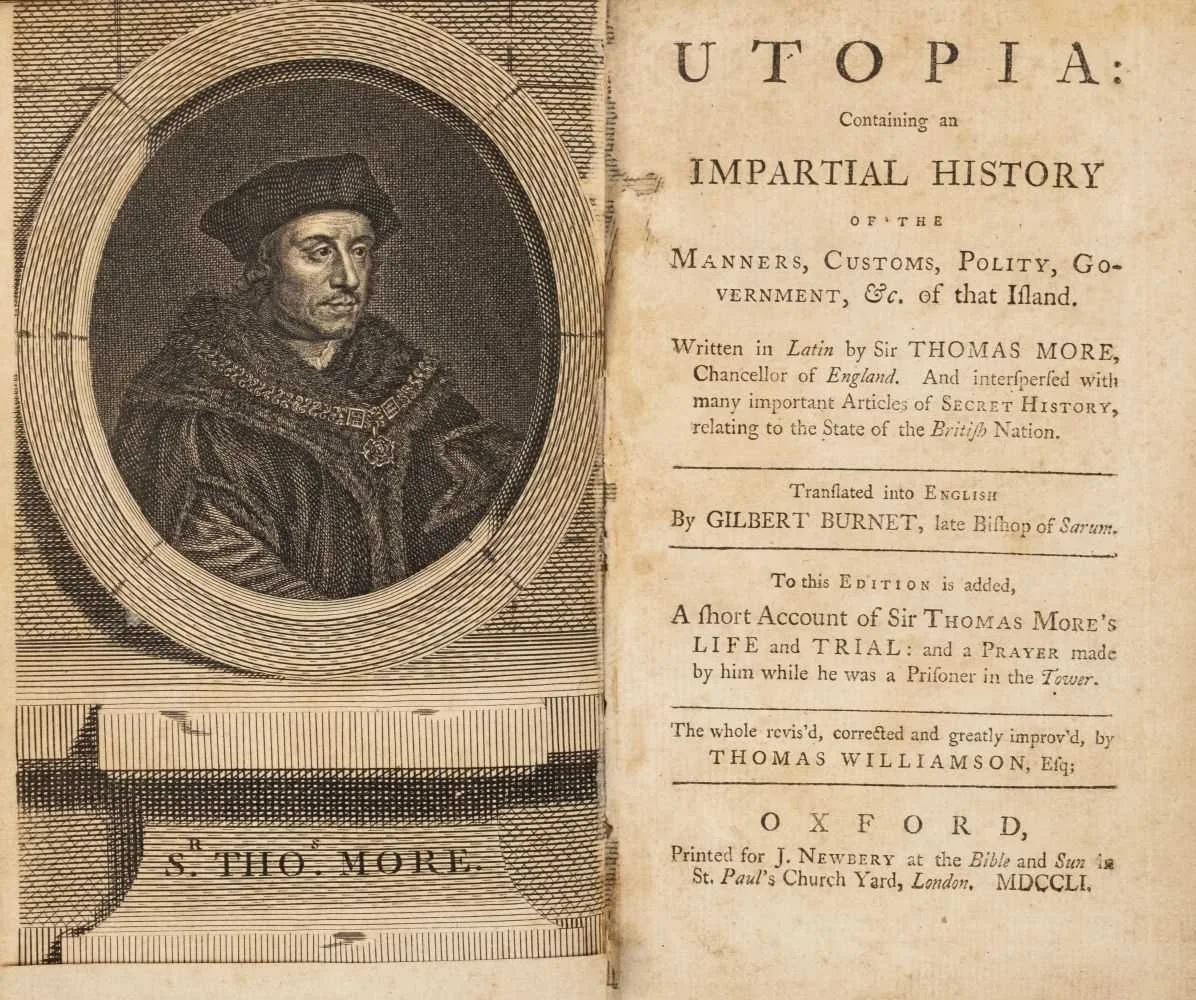

Fig.1 Utopia (uitgave 1751).

Thomas More zag de gelijkheid van de mens als het hoogste goed, terwijl dat voor Machiavelli vooral de vrijheid van de mens was.

In zijn Utopia had More het over een denkbeeldige staat waarin alle burgers gelijk waren, waar orde en vrede heersten, waar geen armoede bestond en waar de leider (koning) er onder het toeziend oog van een goddelijk opperwezen voor zorgde dat zijn onderdanen als deugdzame en moreel hoogstaande mensen konden leven (zie fig.1).

Men kan in het Utopia van More het collectivisme van de latere Sovjet-Unie en de slogan van de Franse Revolutie herkennen. Dat die Liberté, Egalité & Fraternité uiteindelijk mislukt zijn en tot de uitwassen geleid hebben is genoegzaam bekend.

Voor More kon de gelijkheid van de burgers zelfs de noodzaak zijn voor het beperken van de individuele vrijheid en dat was absoluut niet het geval bij Machiavelli. Voor hem was de vrijheid in een samenleving (op alle gebieden) het allerbelangrijkste. Ongelijkheid was niet goed te praten maar volgens Machiavelli bleef er altijd ongelijkheid bestaan op biologisch, politiek, sociaal en economisch vlak. Zijn realisme staat in schril contrast met het idealisme (utopisme) van More. Soms worden de termen utopie en dystopie tegenover elkaar geplaatst maar men kan in het geval van de realpoliticus Machiavelli niet echt spreken van een dystopie, want dat is een denkbeeldige samenleving waarin zich enkel maar negatieve verschijnselen voordoen.

In Utopia was alles gereglementeerd en was alles in feite eenheidsworst. Met het overdreven hanteren van regeltjes had Machiavelli reeds kennis gemaakt tijdens het bewind van Savonarola en dat was hem (en de rest van de Florentijnen) uiteindelijk niet zo erg bevallen. Het opleggen van een verplicht te volgen morele code (en de mensen zoals in Utopia vrij van zonden te maken) was volgens Machiavelli niet houdbaar want de mens is een wezen met passies. Voor hem (en dat was gelinkt aan zijn eigen ervaring) moesten de “geneugten des levens“ (drank, gokken, hoererij) zeker niet afgeschaft worden.

In Utopia mocht niemand er bovenuit steken, maar toch werd de staat bestuurd door een intellectuele elite (cfr.de aristoi of de “besten” van Plato). In dat opzicht was Machiavelli gedeeltelijk dezelfde mening toegedaan: bekwaamheid moest de maatstaf zijn voor de bestuurders, maar niet de afkomst, zoals dat het geval was in een aristocratie of oligarchie, die hij ook zelf had meegemaakt (zie art. Waarom Niccolò Machiavelli nooit verkozen werd in de Florentijnse magistratuur).

Bovendien vond Machiavelli dat iedere (weliswaar verstandige) burger moest kunnen deelnemen aan het bestuur (jong of oud, arm of rijk). Dat neigt enigszins naar democratie, maar dat was het niet want vrouwen en slaven vielen uit de boot. Ook in More’s Utopia was slavernij toegelaten en moesten de vrouwen onderdanig blijven aan de man, zodat het gelijkheidsprincipe (zoals wij dat nu kennen) hier toch ook ver te zoeken was.

Fig.2 illustratie van Eko uit Machiavelli, on politics and power.

Machiavelli voerde het vrijheidsideaal hoog in zijn vaandel. In zijn Discorsi schreef hij dat de vrijheid zelfs bij uitzondering zou kunnen eisen dat men er zijn eigen bloed voor opoffert of van de wet afwijkt. Vrijheid voor Machiavelli betekende ook vrijheid van meningsuiting en godsdienst. Dat hij rad van tong en scherp van pen was is geweten en vrijheid van godsdienst hield voor hem in dat men atheïsme niet kon verbieden. More was dan weer een diepgelovig en vroom man, die voor zijn katholieke overtuiging ook gestorven is, maar Machiavelli had het christelijk wereldbeeld, met een alles overheersende God en het nastreven van de christelijke deugden, overboord gegooid (zie fig.2).

Hij had geen goed woord over voor de geestelijkheid, die hij als een instrument van vrijheidsbeknotting beschouwde. Van Thomas More kreeg de geestelijkheid wel een aparte en dominante plaats in de maatschappij (die zij toen in Engeland en Italië nog steeds innam) zodat er in Utopia in beperkte mate van een theocratie kan gesproken worden.

Volgens Machiavelli moest ook de politiek zich losmaken van het christelijk ideaal: een heerser moest zorgen voor het welzijn en de veiligheid van zijn burgers en niet voor hun zielenheil. Dat hij daar dan soms ook minder aangename, totalitaire (niet-christelijke?) beslissingen moest voor treffen, was niet te vermijden, maar tot een echte tirannie mocht dat niet evolueren.

Op die manier komt men vervolgens tot een mogelijke tegenstelling tussen vrijheid en veiligheid. In het aanschijn van een dreigende ziekte (in Machiavelli’s tijd de pest) zoals de recente covid-19 pandemie zal de overheid (ook in een democratie) soms dwingende maatregelen moeten nemen zonder echter de vrijheid van de burgers al te lang en veel te zwaar te beperken.

In het irreële Utopia waren er uiteraard geen ziekten, maar in de reële wereld van Machiavelli zou een algemene lock-down (moest die bestaan hebben) geen uitzondering geweest zijn en in dat opzicht zou dus de enige beperking van Machiavelli’s vrijheid de veiligheid kunnen zijn. Ook een oorlog was soms niet te vermijden en zelfs noodzakelijk om die veiligheid te garanderen.

Indien Firenze in zijn tijd zou geconfronteerd zijn geworden met een omvangrijke vreemde instroom (die niets te maken had met de komst van buitenlandse bankiers, zakenlui of diplomaten) zou Machiavelli ongetwijfeld een zeer strenge aanpak gesuggereerd hebben. In dat geval kwam de veiligheid tegenover de menselijkheid te staan, maar met dat laatste werd in het Firenze van de 16de eeuw toch al weinig rekening gehouden. Dat had Niccolò tijdens zijn gevangenschap in 1513 zelf mogen ondervinden (zie art. De stoutmoedigheid en durf van Niccolò Machiavelli).

Terwijl er in het Utopia van More (waar iedereen gelukkig en tevreden was) geen partijen bestonden, tenzij een soort eenheidspartij (zoals in de latere communistische regimes) vond Machiavelli een verscheidenheid aan politieke opinies een goede zaak voor het staatsbestel. Dat hij er van overtuigd was dat zijn zienswijze daarbij de juiste was kan hem niet kwalijk genomen worden. Uitstel en getreuzel (kenmerkend voor het toenmalig Florentijns bestuur) waren aan Machiavelli niet besteed, in tijden van crisis moest de overheid snel en vooral krachtdadig optreden.

Er zullen altijd utopische (naïeve?) dromers zoals Thomas More en keiharde (onmenselijke?) realisten zoals Niccolò Machiavelli blijven bestaan en wellicht is dat maar goed ook.

Misschien zou de slogan van de Franse Revolutie in onze tijd geactualiseerd kunnen worden tot “Vrijheid, gelijkheid, veiligheid en menselijkheid” waarbij de orde van belangrijkheid kan bepaald worden in het kader van de politieke overtuiging en/of naargelang van de omstandigheden.

Dan moet echter de overheid de juiste balans kunnen vinden en de 4 items überhaupt in voldoende mate weten te beschermen zonder de verzuchtingen van de onderdanen te negeren…

JVL

Equality or freedom, Thomas More vs. Niccolò Machiavelli.

For the contemporaries Thomas More (1478-1535) and Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), the failure of politics, the social abuses and the corruption in the Western societies in which they lived (respectively early 16th century England and Italy) caused them to criticize the situation in their writings. More did so in his satirical work Utopia (from 1516) and Machiavelli in several political works, of which the Prince (from 1513) is best known.

Thomas More saw the equality of man as the highest good, while Machiavelli gave priority to the freedom of man.

In his Utopia, More described an imaginary state in which all citizens were equal, where order and peace reigned, where there was no poverty, and where the leader (king) under the watchful eye of a supreme divinity ensured that his subjects could live as virtuous and moral people. One can recognize in the Utopia of More the collectivism of the later Soviet Union and the slogan of the French Revolution. It is, however, well known that Liberté, Egalité & Fraternité ultimately failed and led to inevitable excesses.

For Thomas More, the equality of citizens could even be the necessity for restricting individual freedom, and that was absolutely not the case with Machiavelli, because freedom in a society (in all areas) was in his opinion the most important thing. Inequality could not be justified, but according to Machiavelli, inequality could not be excluded on the biological, political, social and economic levels. His realism is in stark contrast to More's idealism (utopianism). Sometimes the terms utopia and dystopia are contrasted, but with Machiavelli one cannot really speak of a dystopia, because that is an imaginary society in which only negative things prevail.

In Utopia, everything was regulated and everything was basically uniform. Machiavelli had already become acquainted with the excessive use of rules during the reign of Savonarola and in the end he (and the rest of the Florentines) did not like it so much. According to Machiavelli, imposing a mandatory moral code (to make people free of sin as in Utopia) was not tenable because man lives with passions. For him (and this was linked to his own experience) the "pleasures of life" (drinking, gambling, fornication) certainly did not have to be abolished.

In Utopia, no one could stand out, yet the state was governed by an intellectual elite (cfr.de aristoi or the "best" of Plato). In this respect, Machiavelli was partly of the same opinion: competence should be the measure of leadership, but not the origin as was the case in an aristocracy or oligarchy which he himself had experienced (see art. Why Niccolò Machiavelli was never elected to the Florentine magistracy).

Moreover, Machiavelli believed that every (intelligent) citizen should also be able to participate in the government (young or old, rich or poor). That leans somewhat towards democracy, but women and slaves were not included. Even in More's Utopia slavery was allowed and women had to remain submissive to men, so that the real principle of equality (as we know it today) was far away.

In Utopia, everything was regulated and everything was basically uniform. Machiavelli had already become acquainted with the excessive use of rules during the reign of Savonarola and in the end he (and the rest of the Florentines) did not like it so much. According to Machiavelli, imposing a mandatory moral code (to make people free of sin as in Utopia) was not tenable because man lives with passions. For him (and this was linked to his own experience) the "pleasures of life" (drinking, gambling, fornication) certainly did not have to be abolished.

In Utopia, no one could stand out, yet the state was governed by an intellectual elite (cfr.de aristoi or the "best" of Plato). In this respect, Machiavelli was partly of the same opinion: competence should be the measure of leadership, but not the origin as was the case in an aristocracy or oligarchy which he himself had experienced (see art. Why Niccolò Machiavelli was never elected to the Florentine magistracy).

Moreover, Machiavelli believed that every (intelligent) citizen should also be able to participate in the government (young or old, rich or poor). That leans somewhat towards democracy, but women and slaves were not included. Even in More's Utopia slavery was allowed and women had to remain submissive to men, so that the real principle of equality (as we know it today) was far away

Machiavelli thought highly of the idea of freedom. In his Discorsi he wrote that freedom could even exceptionally demand to sacrifice one's own blood or even break the law. Freedom for Machiavelli also meant freedom of speech and religion. It is known that he had a sharp tongue and a sharp pen, and in the eyes of Niccolò freedom of religion meant that atheism could not be forbidden.

More, on the other hand, was a deeply religious and pious man, who eventually died for his Catholic convictions, but Machiavelli had abandoned the Christian worldview, with an almighty God and the pursuit of Christian virtues. He had nothing good to say about the clergy, whom he regarded as an instrument of deprivation of liberty. Thomas More gave the clergy a separate and dominant place in society (which they still occupied in England and Italy at the time) so that one could speak of a limited theocracy in Utopia.

According to Machiavelli, politics also had to break away from the Christian ideal: a ruler had to take care of the well-being and safety of his citizens and not of their salvation. Totalitarian (non-Christian?) measures were sometimes unavoidable, but that could not lead to tyranny.

In this way, a possible contradiction arises between freedom and security. In the face of an imminent disease (in Machiavelli's time the plague) such as the recent covid-19 pandemic, the government (even in a democracy) will sometimes have to take coercive measures without, however, restricting the freedom of citizens for too long and too heavily.

In unreal Utopia, of course, there were no diseases, but in the real world of Machiavelli, a general lock-down (if it had existed) would not have been an exception, and in that respect the only restriction of Machiavelli's freedom could be security. A war was also sometimes unavoidable and even necessary to guarantee that security.

If Florence in his time had been confronted with a large foreign influx (which had nothing to do with the arrival of foreign bankers, businessmen or diplomats), Machiavelli would undoubtedly have suggested a very severe approach. In that case, security trumps humanity, but the latter was not taken into account in 16th century Florence anyway as Niccolò had experienced during his imprisonment in 1513 (see art. The boldness and the audacity of Niccolò Machiavelli).

While in More's Utopia (where everyone was happy and content) there were no political parties, except for some kind of unity party (as in the later communist regimes), Machiavelli considered a variety of political opinions a good thing for the state and he cannot be blamed for the fact that he was convinced that his view was the right one. Procrastination and delay (characteristic of the Florentine government) were not Machiavelli’s thing; in times of crisis the government had to act quickly and above all decisively.

There will always be utopian (naïve?) dreamers like Thomas More and hard-hitting (inhuman?) realists like Niccolò Machiavelli, and that is not a bad thing.

Perhaps the slogan of the French Revolution could be updated in our time to "Freedom, equality, security and humanity" in which the order of importance can be determined according to political opinion and/or circumstances. But then the government must also be capable to find the right balance between the 4 items and be able to protect them without neglecting the aspirations of the subjects…

Literatuur:

Anderson, J. Machiavelli. On Politics and Power. New York, 2021.

Barincou, E. Machiavelli in zijn tijd. Utrecht-Antwerpen, 1959.

Beekman, T. Machiavelli’s lef. Amsterdam, 2020.

Unger, J. Machiavelli. Een biografie. Amsterdam, 2012.

Van Laerhoven, J. zie art. De stoutmoedigheid en durf van Niccolò Machiavelli.

zie art. Waarom Niccolò Machiavelli nooit verkozen werd in de

Florentijnse magistratuur.