Moord in de kathedraal (26/4/1478)

Moord in de kathedraal (26/4/1478)

Op basis van teksten (o.a. van Machiavelli en Guicciardini) en ooggetuigenverslagen (Poliziano en Landucci) werd een poging gedaan om een overzicht te maken van de gebeurtenissen van 26 april 1478 (de 5de zondag na Pasen en een uitzonderlijke dag in de geschiedenis van Firenze) toen er een aanslag gepleegd werd op de Medici-broers tijdens de fameuze Pazzi-samenzwering.

Wie waren de leiders van de samenzwering?

Paus Sixtus IV was samen met Girolamo Riario (zijn neef en heer van Forli), koning Ferrante van Napels, Federico da Montefeltro (heer van Urbino), bisschop Francesco Salviati en bankier Francesco de’ Pazzi betrokken in de conspiratie (zie artikel over de Oorzaken van de Pazzi-samenzwering).

Wie waren de andere complotteurs en uitvoerders?

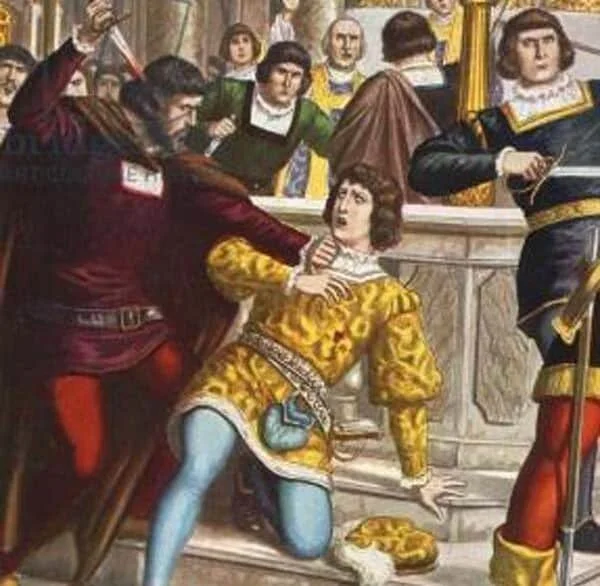

Montesecco, Salviati, Baroncelli, Francesco de’ Pazzi (afb. uit La Congiura dei Pazzi van Cesare Mussini, 1843)

Nadat hij zich had laten overhalen tijdens een persoonlijk gesprek met de paus werd ook Gian Battista da Montesecco, de kapitein van de pauselijke garde, bereid gevonden zich bij het complot aan te sluiten. Verder hadden de samenzweerders ook nog een beroep gedaan op Bernardo Bandini Baroncelli, een avonturier die veel schulden had bij de Pazzi-bank; Jacopo di Poggio Bracciolini, een vriend van Salviati en van Riario; 2 priesters, Antonio Maffei uit Volterra die zijn stad wilde wreken voor de bestraffing in 1472 waarvoor Lorenzo verantwoordelijk werd gesteld en Stefano da Bagnone, de tutor van de dochter van Jacopo de’ Pazzi, en tenslotte ook nog een zekere Napoleone Francezi, wiens rol in de zaak vrij onduidelijk is gebleven.

Wat vooraf ging:

Aangezien Lorenzo zich niet had laten verleiden om met Pasen naar Rome op audiëntie bij de paus te komen, hadden de complotteurs besloten om de aanslag in Firenze te laten gebeuren en de 2 broers samen om te brengen. Paus Sixtus IV wenste uiteraard niet genoemd te worden in de hele zaak (zijn betrokkenheid werd achteraf bevestigd in de bekentenis van Montesecco), maar hij had gezorgd voor een geschikte opportuniteit door zijn 18-jarige neef Raffaele Riario, die hij pas tot kardinaal had verheven, eind maart 1478 naar Firenze te sturen. De Medici-broers moesten zorgen voor een passende ontvangst en Lorenzo dacht waarschijnlijk nog dat het een soort van verzoeningspoging vanwege de paus was. Riccardo Fubini maakte in zijn Congiura dei Pazzi de vergelijking met het binnen halen van het Paard van Troje.

Kardinaal Raffaele Riario logeerde samen met bisschop Salviati (en hun gevolg) in de villa van Jacopo de’ Pazzi in Montughi. Toen Lorenzo het gezelschap uitnodigde in de nabijgelegen Medici-Villa van Fiesole, besloten de samenzweerders om daar hun slag te slaan en de beide Medici-broers te vergiftigen. Over de juiste datum van dit banket is geen eensgezindheid: voor sommige auteurs was het op zondag 19 april, voor anderen op zaterdag 25 april. Toen Giuliano echter niet in Fiesole kwam opdagen wegens ziekte, nodigde Lorenzo het gezelschap uit om de volgende zondag (26 april) de mis bij te wonen in de kathedraal van Firenze en daarna samen te gaan lunchen in het Palazzo Medici.

Met de komst van Raffaele Riario naar Firenze werd de waakzaamheid van de Medici verzwakt (er kwam een grote groep “vreemd volk” in de stad want iedereen had zijn escortes en gevolg bij), zodat de samenzweerders nu een geschikte gelegenheid zouden krijgen om toe te slaan.

Niccolò Machiavelli vertelt dat er op zaterdagavond en nacht druk vergaderd werd in Montughi om de aanslag de volgende dag (zondag 26 april) te laten doorgaan. Francesco Guicciardini (die geen data vermeldt) schrijft dat de samenzweerders besloten om op zondag niet te wachten tot na de lunch, waar Giuliano wellicht toch weer afwezig zou blijven, maar de moord te plegen in de kathedraal tijdens de mis, waar de beide broers zeker verwacht werden.

De paniek sloeg toe bij de complotteurs toen Montesecco plotseling weigerde om een moord te plegen in een kerk, zodat ze op het laatste nippertje op zoek moesten gaan naar vervanging die ze vonden in de persoon van Stefano da Bagnone en Antonio Maffei.

Rekening houdend met de verschillende data van de eerste bijeenkomst in Fiesole (19 of 25 april) zat er dus bijna een ganse week of slechts één dag tussen de 1ste en de 2de moordpoging. Als men er vanuit gaat dat de samenzweerders slechts enkele uren hadden (van zaterdagmiddag 25 tot zondagmorgen 26 april) om hun plannen bij te sturen moesten de vervangers van Montesecco direct gevonden worden zodat men kan veronderstellen dat de 2 priesters in reserve waren gehouden en dus direct konden ingeschakeld worden. Met slechts één dag verschil konden de troepen die onderweg waren (zie art. Federico da Montefeltro en de Pazzi-oorlog) nog enkele uren on hold gezet worden, wat in het andere geval (één week verschil) praktisch onmogelijk geweest was. Meer dan waarschijnlijk is het banket in Fiesole dus doorgegaan op zaterdag 25 april, de dag vóór de aanslag, zoals ook bevestigd wordt door Machiavelli.

De aanslag:

Kardinaal Riario was op zondagmorgen 26 april vroeg vertrokken uit Montughi en was met zijn gevolg rechtstreeks naar het Palazzo Medici gegaan, waar hij zijn rijkleding ruilde voor zijn kerkelijke gewaden. Lorenzo was reeds in de kerk, maar keerde terug naar de Via Larga, waar hij Riario en Montesecco kon begroeten. Toen Lorenzo en de kardinaal (met hun begeleiders) naar de kathedraal stapten, voegden zich de Salviati’s en de Pazzi’s bij de lange stoet.

Kronikeur Piero Parenti vertelt dat Montesecco achteraf gezegd had dat hij naast Lorenzo wilde gaan wandelen om hem van het naderend onheil op de hoogte te brengen (en dus de hele zaak te verraden), maar dat hij daartoe de kans niet gekregen had. Enkele van zijn soldaten hielden de Porta alla Croce bezet (als eventuele vluchtroute) en de rest van zijn 80 mannen had zich verspreid in de stad, waar nog veel ander “vreemd” krijgsvolk rondliep.

In de kerk bracht Lorenzo Raffaele naar een speciale zetel die dichtbij het altaar geplaatst was, terwijl hijzelf aansloot bij een groepje vrienden dat rechts van het altaar stond (aan het zuidelijk transept).. Toen Francesco de’ Pazzi en Bernardo Bandini merkten dat Giuliano er weer niet bij was, gingen zij hem ophalen in het Palazzo Medici. Giuliano was met veel tegenzin meegegaan, omdat hij zich nog ziek voelde, en had weinig of geen beschermende kledij of wapens meegenomen. Dat had Francesco Pazzi vastgesteld toen hij hem zogezegd vriendschappelijk omarmde tijdens hun wandeling naar de dom. Door al dat heen-en weergeloop was de mis met vertraging begonnen (het middaguur was reeds lang gepasseerd) maar de samenzweerders waren vastberaden om hun plannen door te zetten.

Onder het voorwendsel dat hij zijn zieke moeder ging bezoeken was Francesco Salviati in gezelschap van Bracciolini en zijn escorte (bestaande uit een 20-tal mannen meestal uit Perugia) naar het Palazzo Vecchio getrokken om daar de situatie na de aanslag onder controle te houden.

Francesco de’ Pazzi doodt Giuliano (T. Scarpelli in: P. Giudici, Storia d’ Italia, 1931)

In de kerk zelf had Giuliano zich intussen met zijn 2 begeleiders bij een groepje gevoegd dat aan de noordelijke kant van het altaar stond. Rond 3 uur sloegen de aanvallers op het afgesproken teken (volgens sommige bronnen het opheffen van de hostie) toe: Bandini en Pazzi sprongen op Giuliano af en brachten hem verscheidene messteken toe. Giuliano werd door Baroncelli zwaar in het hoofd geraakt en kreeg daarna van Francesco de' Pazzi de volle laag: in totaal kreeg hij 19 dolksteken en Pazzi ging daarbij zodanig tekeer dat hij zichzelf aan het been kwetste.

Lorenzo had meer geluk: door overhaasting mistte Antonio Maffei zijn eerste dolkstoot en Lorenzo die slechts licht geraakt werd aan de hals, kon zich in een eerste reactie beschermen met zijn opgerolde mantel. Met getrokken zwaard sprong hij over de koorafsluiting en vluchtte weg in de richting van de Nieuwe Sacristie (de Sacristia delle Messe).

Baroncelli, die Giuliano overliet aan de razernij van Francesco de' Pazzi en zag dat Lorenzo niet zwaar geraakt was, stormde achter hem aan: op zijn weg bracht hij Francesco Nori (een goeie vriend van de Medici) met één houw een dodelijke verwonding toe en kwetste hij ook nog vrij ernstig Lorenzo Cavalcanti (een schildknaap), maar hij kon niet beletten dat Lorenzo door Angelo Poliziano in de sacristie kon binnen gesleurd worden en achter de zware bronzen deuren bescherming vond.

Uit angst voor vergiftiging werd Lorenzo’s wonde uitgezogen door de behulpzame Antonio Ridolfi, een jonge page van de Medici-hofhouding. Nadat een andere page, Sigismondo della Stufa, gezien had dat de weg vrij was, werd Lorenzo terug naar het Palazzo Medici geleid. Het lichaam van de dode Giuliano lag nog steeds in de kathedraal en werd door leden van de Misericordia (een Florentijnse hulporganisatie) meegenomen en gewassen, zodat Lucrezia Tornabuoni, die op de hoogte gebracht was van de calamiteit, vanuit Careggi naar Firenze kon komen om haar dode zoon in haar armen te nemen.

Kardinaal Riario, was te midden van al dat geweld op zijn knieën gaan zitten bidden vóór het altaar. Toen Giuliano dood op de kerkvloer lag en Lorenzo al de Nieuwe Sacristie (aan de noordkant van de kerk) was binnengevlucht bekommerden enkele kanunniken van de kathedraal zich om de bevende prelaat en brachten hem naar de Oude Sacristie (aan de zuidkant). De kerk, waar duizenden Florentijnen waren bijeen gekomen, was ondertussen leeg gelopen en de kanunniken leverden Riario uit aan 2 leden van de 8 van de Veiligheid die hem naar het Palazzo Vecchio brachten waar hij in verzekerde bewaring werd genomen. Achteraf werd aan Sixtus IV gezegd dat men de kardinaal had moeten beschermen tegen de woedende volksmassa.

Tijdens de mis waren Salviati en Bracciolini met hun bende Perugianen naar het Palazzo Vecchio getrokken waar zij gonfaloniere Cesare Petrucci wilden ontmoeten om hem zogezegd een belangrijk bericht te overhandigen. De banierdrager (een trouwe aanhanger van de Medici) was echter achterdochtig en terwijl hij Salviati en Bracciolini kon ontvangen liet hij hun handlangers ongemerkt in enkele bijvertrekken opsluiten. Wanneer hem het nieuws bereikte van de gebeurtenissen in de dom werden de maskers afgeworpen; Petrucci kon Bracciolini, die een wapen getrokken had, eigenhandig overmeesteren en liet hem samen met Salviati door zijn wachters meteen ophangen aan de ramen van het regeringspaleis. De menigte die na het onophoudelijk gelui van de stadsklokken naar de Piazza della Signoria gestroomd was en van de samenzwering op de hoogte gebracht werd, koelde haar woede op de Perugianen en de aanhangers van de Pazzi, die letterlijk in mootjes gehakt werden.

Lorenzo die inmiddels in het Palazzo Medici was aangekomen werd verder verzorgd maar moest zich tonen aan de samengestroomde volksmassa, die zich nu in alle hevigheid tegen zijn aanvallers keerde. Francesco de' Pazzi werd uit zijn woning gesleurd, waar hij de wonde aan zijn been aan het verzorgen was, en in het Palazzo Vecchio opgehangen naast bisschop Salviati. Lorenzo's aanvallers, Antonio en Stefano die aanvankelijk in het tumult uit de dom waren kunnen ontkomen, werden uit de kerk van de Badia gehaald, gecastreerd en met afgesneden neus en oren aan de 8 van de veiligheid overhandigd. Daarna werden ze opgehangen.

Jacopo de' Pazzi, die naar Castagno di San Godenzo gevlucht was, werd door de inwoners uitgeleverd en in Firenze opgehangen naast Francesco. Ook zijn broer, Renato de’ Pazzi, die de actie nochtans niet gesteund had, viel ten prooi aan de volkswoede. Guglielmo de’ Pazzi, de broer van Francesco, was uit de dom naar het Palazzo Medici gevlucht: hij werd enkel gestraft met een verbanning (zie artikel i.v.m. Guglielmo de’ Pazzi).

Aan het eind van de dag was het verdict verschrikkelijk: Giuliano de’ Medici was vermoord, een bisschop was opgehangen en een kardinaal gevangen gezet. Samen met verschillende leden van de Pazzi-familie waren de meeste daders op gruwelijke wijze gedood en de Piazza della Signoria lag bezaaid met lijken. Dezelfde avond nog werd Giuliano bijgezet in de crypte van de San Lorenzo.

De nasleep van de gebeurtenissen:

Volgens apotheker-kronikeur Luca Landucci, die alles meegemaakt had en genoteerd in zijn dagboek, was de stad gedurende enkele dagen het toneel geweest van een hele reeks lynchpartijen en bestialiteiten. In totaal zouden er zo’n 270 slachtoffers geteld zijn. Het lijk van Jacopo de’ Pazzi werd zwaar gemutileerd en in de Arno gesmeten.

Gianbattista Montesecco had zich zeer snel uit de voeten gemaakt toen hij zag dat het de verkeerde weg opging, maar hij werd op 1 mei gearresteerd en 4 dagen later onthoofd. Uit zijn geschreven bekentenis werden zeer waarschijnlijk de namen van Ferrante van Napels en Federico da Montefeltro van Urbino geschrapt. Wellicht was dat gebeurd op bevel van Lorenzo zelf, maar dat had niet veel geholpen want 2 maanden later hadden de koning en de hertog de Medici en Firenze in naam van de paus de oorlog verklaard (zie artikel over Federico da Montefeltro en de Pazzi-oorlog).

Bandini kon vluchten naar Constantinopel maar werd in de lente van 1480 door de sultan uitgeleverd aan Lorenzo en in het Bargello opgehangen. Enkel Napoleone Francezi is nooit gevat, maar hij is in dienst van het Napolitaanse leger gesneuveld in 1479.

Raffaele Riario werd door Lorenzo als gijzelaar achter de hand gehouden, hij was tenslotte een familielid van Girolamo Riario en van de paus en pas op 12 juni, toen Sixtus IV dreigde met een interdict, werd hij in vrijheid gesteld en naar Rome gestuurd (zie art. over Riario). De paus liet het daar echter niet bij en verklaarde Firenze en de Medici de oorlog die pas in 1480 beëindigd werd. Het interdict werd opgeheven en een jaar later zouden de goede betrekkingen tussen Lorenzo en Sixtus IV zelfs tijdelijk hersteld worden.

JVL

Murder in the Cathedral (26/4/1478)

On the basis of texts (including Machiavelli and Guicciardini) and eyewitness accounts (Poliziano and Landucci), was made an overview of the events of April 26, 1478 (the 5th Sunday after Easter and an exceptional day in the history of Florence) when a murderous attack was committed on the Medici brothers during the famous Pazzi conspiracy.

Who were the leaders of the conspiracy?

Pope Sixtus IV, along with Girolamo Riario (his nephew and lord of Forli), King Ferrante of Naples, Federico da Montefeltro (Lord of Urbino), Bishop Francesco Salviati and banker Francesco de' Pazzi were involved in the conspiration (see the article about the Causes of the Pazzi conspiracy).

Who were the other plotters and executors?

After being persuaded during a face-to-face meeting with the Pope, Gian Battista da Montesecco, the captain of the Papal Guard, was prepared to join the plot. The conspirators had also appealed to Bernardo Bandini Baroncelli, an adventurer who was in high debt at the Pazzi Bank; Jacopo di Poggio Bracciolini, a friend of Salviati and of Riario; 2 priests, Antonio Maffei from Volterra who wanted to avenge his city for the punishment in 1472 for which Lorenzo was held responsible and Stefano da Bagnone, the tutor of Jacopo de' Pazzi's daughter, and finally a certain Napoleone Francezi, whose role in the case has remained quite unclear.

What preceded:

Since Lorenzo was not going to come to Rome for an audience with the Pope at Easter, the plotters had decided to carry out the attack in Florence and then kill the two brothers at the same time at the same place. Pope Sixtus IV obviously did not wish to be named in the whole affair (his involvement was later confirmed in Montesecco's confession), but he had provided a suitable opportunity by sending his 18-year-old cousin Raffaele Riario, whom he had only recently elevated to cardinal, to Florence at the end of March 1478. The Medici brothers had to provide an appropriate reception and Lorenzo probably thought it was some kind of reconciliation attempt by the Pope. Riccardo Fubini made the comparison with the story of the Trojan Horse in his Congiura dei Pazzi.

Cardinal Raffaele Riario stayed with Bishop Salviati (and their entourage) in the villa of Jacopo de' Pazzi in Montughi. When Lorenzo invited the company to the nearby Medici-Villa of Fiesole, the conspirators decided to make their move there by poisoning the two Medici brothers. The correct date of this banquet is not yet unanimous: for some authors it was on Sunday April 19 for others on Saturday April 25. However, when Giuliano did not show up in Fiesole due to illness, Lorenzo invited the company to attend Mass the following Sunday (April 26) at Florence Cathedral before having lunch together at the Palazzo Medici.

With the arrival of Raffaele Riario to Florence, the vigilance of the Medici was weakened (a large group of "foreign people" came into the city because everyone had his escorts and entourage), so that the conspirators would now have a suitable opportunity to strike.

Niccolò Machiavelli explains that the tension rose in Montughi on Saturday night because the attack was postponed until the next day (Sunday, April 26). Francesco Guicciardini (not mentioning any dates) writes that the conspirators decided not to wait until after lunch on Sunday, where Giuliano might be absent again, but to commit the murder in the cathedral during mass, where the two brothers were certainly expected to be present.

The panic struck the plotters when Montesecco suddenly refused to commit murder in a church, so they had to look for replacements which they found in the person of the 2 priests Stefano da Bagnone and Antonio Maffei.

Taking into account the different dates of the first meeting in Fiesole (19 or 25 April), there was almost a whole week or just one day between the 1st and the 2nd assassination attempt. In the latter case the conspirators had only a few hours (from Saturday afternoon 25 to Sunday morning 26 April) to adjust their plans. Montesecco was replaced immediately by the 2 priests who therefore must have been kept on hand. With only one day difference the troops who were on their way (see art. Federico da Montefeltro and the Pazzi War) were put on hold for a few more hours, which in the other case (one week difference) would have been practically impossible. It is therefore very likely that the banquet in Fiesole took place on Saturday 25, only one day before the attack on Sunday (as testifies also Machiavelli).

The attack:

Cardinal Riario had left Montughi early on Sunday morning April 26 and had gone directly to the Palazzo Medici, where he exchanged his riding clothes for his ecclesiastical robes. Lorenzo was already in the church, but returned to Via Larga, where he met Riario and his companion Montesecco. When Lorenzo and the cardinal (with their entourage) walked towards the cathedral, the Salviati’s and the Pazzi’s joined the long procession.

Chronicler Piero Parenti claims that Montesecco testified afterwards that he was searching Lorenzo’s company to inform him of the coming danger (and thus to betray the whole plot), but that he had not been given the opportunity to do so. Some of his men kept the Porta alla Santa Croce occupied (as a possible escape route) and the rest of his 80 men had spread into the city where many other “strange” armed people were walking around.

Inside the church, Lorenzo accompanied Raffaele to a special seat placed near the altar, while he joined a group of friends standing to the right of the altar (in the southern transept).

When Francesco de' Pazzi and Bernardo Bandini noticed that Giuliano was absent again, they went to pick him up at the Palazzo Medici. He came reluctantly along, pretending that he was still sick, without any protective clothing or weapons as Francesco Pazzi had found out when he friendly embraced him during their walk to the cathedral. Because of all the running back-and-forth, mass had begun with delays (noon had already been passed for a long time) but the conspirators were determined to continue their plans.

Under the pretext that he was going to visit his sick mother, Francesco Salviati left the duomo for the Palazzo Vecchio in the company of Bracciolini and his escort (consisting of about 20 men mostly from Perugia) to take control of the situation after the coup.

Meanwhile Giuliano and his two companions had joined a small group on the northern side of the altar inside the cathedral. Around 3 pm the attackers struck on the agreed sign (according to some sources when the priest was lifting the communion wafer): Bandini and Pazzi assaulted Giuliano and inflicted several stab wounds on him. Giuliano was hit in the head by Baroncelli and then got 19 dagger stitches from a infuriated Francesco de’ Pazzi, who wounded himself in the leg in his frenzy.

Lorenzo had better luck: Antonio Maffei missed his first stab and Lorenzo, who was only slightly hit in the neck, was able to protect himself with his rolled-up cloak. With drawn sword he jumped over the choir fence and fled in the direction of the New Sacristy (the Sacristia delle Messe).).

Baroncelli, who left Giuliano to the fury of Francesco de' Pazzi, saw that Lorenzo was not badly hurt and went after him. On his way he gave Francesco Nori (a close friend of the Medici) with one blow a fatal injury and he also hurt quite badly Lorenzo Cavalcanti (a squire) but he could not prevent that Angelo Poliziano dragged Lorenzo into the sacristy where they found protection behind the heavy bronze doors.

Fearing poisoning, Lorenzo's wound was sucked out by the helpful Antonio Ridolfi, a young page of the Medici court. When another page, Sigismondo della Stufa, saw that the road was clear, Lorenzo was led back to the Palazzo Medici. Giuliano's body that was still in the cathedral was taken away and washed by members of the Misericordia (a brotherhood for the care of the sick and wounded) so that Lucrezia Tornabuoni, who had been informed of the calamity, could come from Careggi to Florence and hold her dead son in her arms.

Cardinal Riario, in the midst of all that violence, sat down on his knees praying in front of the altar. It was only when Giuliano was dead on the church floor and Lorenzo was inside the New Sacristy (on the north side of the duomo) that some canons of the cathedral cared for the trembling prelate and took him to the Old Sacristy (on the south side). Meanwhile the few thousand Florentines that had attended mass had fled the church and the canons handed Riario over to 2 members of the 8 of Security. They accompanied him to the Palazzo Vecchio where he was taken into custody. Afterwards, Sixtus IV was told that the 8 had to protect the cardinal from the raging mob.

During Mass, Salviati and Bracciolini and their escort of Perugians had gone to the Palazzo Vecchio where they wanted to inform gonfaloniere Cesare Petrucci about a so-called important message. However, the standard bearer (a loyal supporter of the Medici) was very suspicious and while he received Salviati and Bracciolini in his office, the Perugians were locked up in a side room.

When the news of the events in the cathedral reached city hall, the masks were cast off: Petrucci was able to overpower Bracciolini, who had drawn a weapon, and ordered his guards to hang Salviati and Bracciolini immediately on the windows of the government palace. The crowd, which had gathered to the Piazza della Signoria after the incessant roaring of the city bell was informed of the conspiracy, and cooled its anger on the Perugians and the Pazzi accomplices who were literally hacked into pieces.

Lorenzo, who was recovering in the Palazzo Medici, had to show himself to the gathered crowd, that went on searching for his attackers. Francesco de' Pazzi was dragged from his home, where he was taking care of the wound on his leg, and hanged in the Palazzo Vecchio next to Bishop Salviati. The 2 priests, Antonio and Stefano, who had initially escaped from the cathedral in the tumult, were captured in the Badia church, castrated and handed over to the 8 of security with their nose and ears cut off. Then they were hanged.

Jacopo de' Pazzi, who had fled to Castagno di San Godenzo, was brought in by the inhabitants and hanged in Florence next to Francesco. His brother, Renato de' Pazzi, who had not supported the action, also fell victim to popular anger. Guglielmo de' Pazzi, Francesco's brother, had fled from the cathedral to the Palazzo Medici: he was only punished with an exile (see article on Guglielmo).

At the end of the day, the verdict was terrible: Giuliano de' Medici had been murdered, a bishop had been hanged and a cardinal arrested. Along with several members of the Pazzi family, most of the perpetrators were brutally killed and the Piazza della Signoria was littered with corpses. The same evening Giuliano’s body was added to the crypt of the San Lorenzo.

The aftermath of the events:

According to pharmacist and chronicler Luca Landucci, who had seen it all and noted in his diary, the city had been the scene of a series of lynching and bestialities for several days. In total, some 270 victims were counted. The corps of Jacopo de' Pazzi was heavily mutilated and thrown into the Arno.

Gianbattista Montesecco left Florence in a hurry when he saw that things were going the wrong way, but he was arrested on May 1 and decapitated 4 days later. From his written confession, the names of Ferrante of Naples and Federico da Montefeltro of Urbino were most likely deleted. Perhaps this was done on Lorenzo's orders, but only 2 months later the king and the duke declared war on the Medici and Florence in the name of the Pope (see article on Federico da Montefeltro and the Pazzi War).

Bandini was able to flee to Constantinople but was extradited by the sultan to Lorenzo in the spring of 1480 and hanged in the Bargello. Only Napoleone Francezi was never captured, but he was killed in the service of the Neapolitan army in 1479.

Raffaele Riario was held hostage by Lorenzo. After all he was the nephew of Girolamo Riario and the Pope, and it was not until June 12, when Sixtus IV issued an interdict on Lorenzo and Florence, that he was released and sent to Rome (see article on Riario). However, the Pope did not leave it at that and declared war on Florence and the Medici that only ended in 1480. The interdict was lifted and a year later the good relations between Lorenzo and Sixtus IV would even be temporarily restored.

Literatuur:

De Mandato, A. Della Congiura de’ Pazzi dell Anno 1478. Commentario di Angelo Poliziano

voltato dal Latino in Toscano , Napoli, 1849.

Falcioni, A. Montesecco, Gian Batista, in: Dizionario biografico, vol.76 (2012).

Fubini, R. Italia quattrocentesca. Milaan, 1994.

Guicciardini, F. The History of Italy. Princeton, 1969.

Landucci, L. Diario Fiorentino dal 1450 al 1516 (Iodoco del Badia, Firenze, 1862)

Machiavelli, N. Istorie Fiorentine, Libro ottavo, cap.5. https://it.wikisource.org/wiki/Istorie_fiorentine

History of Florence. www.gutenberg.com

Martines, L. Bloed in April. Amsterdam, 2005.

Unger, M. The Brilliant Life and Violent Times of Lorenzo de’ Medici. New York, 2008.

Van Laerhoven, J. De Medici en de Pazzi. Kermt, 2019.

zie art. De oorzaken van de Pazzi-conspiratie.

zie art. Federico da Montefeltro en de Pazzi-oorlog.

zie art. Raffaele Riario, schuldig of onschuldig aan de Pazzi-samenzwering?

zie art. Waarom de Pazzi-aanslag mislukt is.

zie art. Was Guglielmo de’ Pazzi betrokken bij de samenzwering van 1478?