Wie is de Mona Lisa?

Wie is de Mona Lisa?

Sedert 2005 wordt algemeen aangenomen dat de Mona Lisa (of La Gioconda) van Leonardo da Vinci te vereenzelvigen is met Lisa Gherardini, de echtgenote van de Florentijnse zijdekoopman Francesco del Giocondo (zie art Leonardo da Vinci, Lisa Gherardini en Francesco del Giocondo). Naast de wereldberoemde Mona Lisa van het Louvre (uit 1513-17) is er ook nog de Mona Lisa van Isleworth uit 1503, die beschouwd wordt als een andere (vroegere) versie (zie art. De Mona Lisa’s van Isleworth en het Louvre).

Beide portretten zijn originele werken van de kunstenaar, waar waarschijnlijk ook zijn leerlingen aan meegewerkt hebben. Het was immers, zeker bij Leonardo, niet ongewoon dat er verscheidene versies van een werk gemaakt werden, weliswaar onder zijn toezicht en met de persoonlijke touch van de meester.

Niet iedereen is er echter van overtuigd dat de dame die Leonardo gepenseeld heeft Lisa del Giocondo is en er zijn de laatste decennia heel wat theorieën naar voor geschoven, die soms wat ver gezocht, maar soms ook verrassend en interessant kunnen zijn.

Fig.1 Sint-Anna ten Drieën (Louvre)

1. Een geïdealiseerd fictief personage:

Misschien is Mona Lisa Leonardo’s ideaal type van mens, zijn schoonheidsideaal, dat een synthese moest zijn van de verschillende mensen (mannen en vrouwen) die hem lief waren. Wie het werk van da Vinci kent kan vaststellen dat zijn Mona Lisa-type geregeld terugkeert als vrouwelijk personage in een aantal andere schilderijen. Zo is er een gelijkenis te vinden met o.a. het onafgewerkte karton met de Heilige Anna (National Gallery) uit 1498 en de Sint-Anna ten Drieën (Louvre) uit 1510 (zie fig.1). Hetzelfde type vrouw verschijnt wellicht ook al op de Madonna van de Rotsen (versie Louvre 1483-86 en versie National Gallery 1491-1508).

De androgyne figuren van da Vinci vertonen zowel vrouwelijke als mannelijke trekken; men denke hierbij aan de figuur van Johannes de Doper (zie verder) en de figuur van Johannes de Apostel op zijn beroemde Laatste Avondmaal.

De theorie van het geïdealiseerd fictief personage is zeer aannemelijk want ook bij andere kunstenaars, zoals bijvoorbeeld Sandro Botticelli, keert dezelfde figuur steeds terug in vele werken. Maar net zoals bij Botticelli is het niet uitgesloten dat het personage toch gebaseerd was op een bestaand iemand.

2. Leonardo’s moeder:

Fig. 2 Mona Lisa = Leonardo

Leonardo was het onwettige kind van notaris ser Piero d’ Antonio da Vinci en een zekere Caterina Lippi, een weesmeisje uit de omgeving dat achteraf werd uitgehuwelijkt aan een plaatselijke boer Antonio Butti. De knaap werd echter door zijn vader, toen die trouwde met Albiera Amadori, opgenomen in het gezin. Het is echter moeilijk aan te nemen dat de afgebeelde dame de vrouw van lage komaf zou zijn die zijn moeder hoogst waarschijnlijk geweest is.

3. Leonardo zelf:

Omwille van de gelijkenis met een later zelfportret (uit de Biblioteek van Turijn) zou men in de figuur van Mona Lisa de gelaatstrekken van Leonardo zelf kunnen herkennen (zie fig.2). Het blijft altijd mogelijk dat de kunstenaar (die homofiel of biseksueel was) zijn vrouwelijke kant heeft willen vastleggen. Deze visie sluit ook aan bij de bewering dat de Mona Lisa een portret van zijn moeder zou zijn.

4. Andrea Salai (Gian Giacomo Caprotti di Oreno):

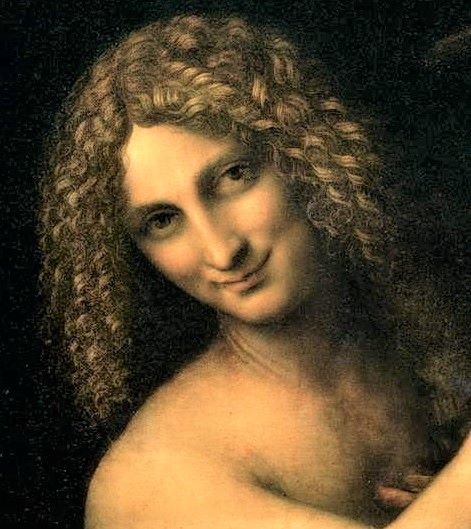

Fig.3 Johannes de Doper (Louvre)

Er is ook een zeer sterke gelijkenis merkbaar tussen de Mona Lisa en de figuur van Sint-Jan de Doper (1513-16) uit het Louvre waarvan men veronderstelt dat zijn leerling (en minnaar?) Andrea Salai er model voor gestaan heeft (zie fig.3). Salai was reeds van zijn 10 jaar in het atelier van Leonardo en is 30 jaar lang zijn metgezel gebleven. Het schilderij met de Sint-Johannes bevond zich volgens het dagboek van Andrea de Beatis, (de secretaris van kardinaal Louis van Aragon, die Leonardo in 1517 in Frankrijk bezocht had) samen met het portret van een Florentijnse dame en de Sint-Anna ten Drieën in 1517 in de woning van Leonardo in Clos-Lucé, waar Salai met hem samenwoonde.

Salai zou volgens sommige auteurs zelfs de co-auteur van (één van) de Mona Lisa’s kunnen geweest zijn. Hij zou ook model gestaan hebben voor de Monna Vanna (“De ijdele vrouw of ook de Naakte Mona Lisa” genoemd), een houtskool schets die in de studio van da Vinci gemaakt is en ook bewaard wordt in het Louvre. De gelijkenis met de Mona Lisa is overduidelijk (zie fig.4).

Fig. 4 Monna Vanna (Louvre)

Deze theorie sluit aan bij het geïdealiseerd man-vrouw-type. Net zoals bij de beelden van Michelangelo in de Nieuwe Sacristie van San Lorenzo zijn aan de mannelijke torso (met gespierde armen) borsten aan toegevoegd.

Om te bewijzen dat Salai wel degelijk model gestaan heeft voor de Mona Lisa hebben sommige “kunstkenners” aangevoerd dat Mona Lisa een anagram is voor Mon Salai. Zij vergeten dan echter wel dat Monna Lisa (afkorting van madonna Lisa) eigenlijk met dubbele n geschreven wordt.

Op de oogleden van Mona Lisa zouden volgens Silvano Vinceti de letters L(Leonardo) en S (Salai) te vinden zijn, maar dat lijkt eerder wishful thinking (zie verder).

5. Pacifica Brandano, Isabella Gualanda of Costanza d’ Avalos:

Wanneer Andrea de Beatis sprak over het portret van een “zekere Florentijnse dame, die in vivo geschilderd was in opdracht van wijlen Giuliano de’ Medici” zou daarmee volgens sommigen één van de minnaressen van Giuliano (de jongste zoon van il Magnifico) bedoeld zijn. Dat zouden dan Pacifica Bradano, Isabella Gualanda of Costanza d’Avalos moeten zijn. Giuliano zou van Pacifica een portret hebben laten maken in 1511 toen zij kort na de geboorte van hun zoontje Ippolito gestorven is (zie art. De mysterieuze dood van Ippolito de’ Medici) . Giuliano is zelf overleden in 1516 vooraleer het portret voltooid was. Er was dus geen koper meer en misschien heeft Leonardo het portret overschilderd met de Mona Lisa zoals we ze nu kennen.

Pacifica was afkomstig uit Urbino, zodat het weinig waarschijnlijk is dat zij de Florentijnse dame was. Dat het Isabella Gualanda uit Napels zou zijn, die de Beatis in zijn dagboek wel vermeldt, maar niet uitdrukkelijk als de minnares van Giuliano, is zeer twijfelachtig en dat het Costanza d’Avalos, de hertogin van Francavilla zou zijn, die Giuliano blijkbaar niet eens kende, is bijzonder ongeloofwaardig.

Maar het is echter niet uitgesloten dat Giuliano (toen Leonardo in 1513 in zijn dienst was getreden in Rome) een portret heeft laten maken van zijn “goede vriendin” Lisa del Giocondo, die hij nog kende van in zijn jeugd (zie Leonardo da Vinci, Lisa Gherardini en Francesco del Giocondo). Op die manier zou het dan toch een schilderij van een Florentijnse dame kunnen geweest zijn, van wie de kunstenaar de identiteit blijkbaar niet aan De Beatis had kenbaar gemaakt.

6. Fioretta Gorini:

Volgens Angelo Paratico zou de mysterieuze Florentijnse dame Fioretta Gorini geweest zijn, de minnares van Giuliano de’ Medici, de broer van Lorenzo il Magnifico, die in april 1478 tijdens de Pazzi-aanslag is vermoord geworden. Leonardo zou het tijdens het gesprek met de kardinaal van Aragon en Andrea de Beatis dus niet over wijlen Giuliano, hertog van Nemours, gehad hebben, maar over diens overleden oom met dezelfde naam. Die zou dan opdracht gegeven hebben aan de jonge Leonardo om in 1477/78 Fioretta’s portret te schilderen toen zij in verwachting was. Kort na de geboorte van haar zoontje Giulio (de later paus Clemens VII) is zij echter in datzelfde 1478 overleden. Dat hij toen al in staat was om een dergelijk werk te penselen had Leonardo bewezen met het portret van Ginevra de’ Benci (uit de National Gallery) dat hij rond dezelfde tijd geschilderd had en waarvan trouwens ook gezegd wordt dat het Fioretta zou zijn.

Aangezien opdrachtgever en geportretteerde dood waren heeft Leonardo het schilderij dan maar bij zich gehouden.

Een weinig doorslaggevend argument voor de datering is dat Leonardo populierenhout gebruikt heeft voor het portret en daarna pas tijdens zijn Milanese periode naar notelaar is overgeschakeld.

Het portret moet dus, in tegenstelling met wat o.a. Vasari geschreven heeft, niet in 1503, maar al 25 jaar eerder geschilderd zijn. Fioretta was toen 24 jaar en de dame op het portret uit het Louvre is echter reeds ouder. De bevindingen van Pascal Cotte die onder de Mona Lisa van het Louvre een eerder geschilderde figuur van een jongere vrouw ontdekt heeft, zou dan bevestigen dat het portret vroeger kan gemaakt zijn. Maar met wiens portret Fioretta dan overschilderd is geworden is niet duidelijk. Vooral omwille van de chronologie is deze theorie niet erg overtuigend.

7. Lisa del Giocondo del Giocondo:

Aangezien Vasari nergens uitdrukkelijk de naam Lisa Gherardini vermeldt, maar enkel spreekt over Lisa del Giocondo beweert Giuseppe Pallanti dat het gaat over de zus van Francesco, die dus ook del Giocondo heette en niet Gherardini. Zij was getrouwd met haar neef, ook een Francesco (of Pierfrancesco) del Giocondo en ook een zijdehandelaar.

Enerzijds valt er voor deze theorie wel wat te zeggen, want in de renaissance was het gebruikelijk dat vrouwen hun eigen familienaam behielden, maar anderzijds zou deze Lisa (geboren in 1468) in 1503 al 35 en in 1517 al 49 jaar geweest zijn en is het dus weinig waarschijnlijk dat zij de dame van het portret geweest is. Een verklaring kan zijn dat Vasari het wellicht niet nodig gevonden heeft om Lisa’s meisjesnaam Gherardini te vermelden.

Alleszins merkwaardig is dat Agostino Vespucci (neef van Amerigo en medewerker van Niccolò Machiavelli) in zijn aantekening van oktober 1503 op een werk met “Brieven van Cicero” uit de universiteitsbibliotheek van Heidelberg (zie art. de Mona Lisa’s van Isleworth) ook spreekt over een schilderij dat Leonardo gemaakt had van “Lise del Giocondo” (en niet van Lise Gherardini…).

8. Cecilia Gallerani en Lucrezia Crivelli:

Fig. 5 Cecilia Gallerani & Lucrezia Crivelli

Het portret van Cecilia Gallerani is ook bekend als de Dame met de Hermelijn en is bewaard in het Museum van Krakau en het portret van Lucrezia Crivelli uit het Louvre (zie fig.5) wordt daar ook La Belle Ferronnière genoemd. Er is misschien wel enige gelijkenis te bespeuren met de Mona Lisa, maar beide dames worden echter geïdentificeerd als minnaressen van hertog Ludovico Sforza en zijn door Leonardo tijdens zijn Milanese periode geportretteerd (tussen 1489 en 1496). La Belle Ferronnière is misschien ook een portret van Beatrice d’Este, de echtgenote van Sforza. De moeilijk te herkennen letters (B?) S op het ooglid van Mona Lisa zouden volgens prof. Vinceti ook kunnen verwijzen naar deze Beatrice Sforza.

9. Caterina Sforza en Isabella d’ Este:

Fig. 6 Caterina Sforza (L.di Credi, Forli)

Ook van Caterina Sforza, de gravin van Forli, wordt gezegd dat zij de Mona Lisa zou zijn. Maar haar portret als la dama dei Gelsomini wordt toegeschreven aan Lorenzo di Credi (zie fig.6). Het dateert uit 1481/82 en wordt bewaard in de Pinacoteca van Forli. Als men dit schilderij vergelijkt met de Mona Lisa moet men toch constateren dat het om een andere vrouw gaat (zie art. Caterina Sforza, de tijgerin van Forli).

Toen Leonardo in 1499 in Mantua passeerde vroeg markiezin Isabella d’ Este hem om haar portret te maken. In het Louvre is de voorbereidende tekening (in profiel) bewaard, waarvan men denkt dat ze van Leonardo is en die inderdaad overeenkomsten vertoont met het portret van Mona Lisa (pose, kin, handen en haar). Met latere afbeeldingen van Isabella d’Este zijn er weinig gelijkenissen te vinden.

Fig. 7 Isabella d’ Este – Mona Lisa (Louvre)

De tekening moet dan 3 à 4 jaar vroeger gemaakt dan de 1ste Mona Lisa, waarvan Vasari zegt dat het Lisa del Giocondo is. Het is wel mogelijk dat Leonardo zijn portret van Lisa enigszins zou gebaseerd hebben op de schets van Isabella (zie fig.7). Maar om de Mona Lisa uit het Louvre te kunnen identificeren met Isabella d’ Este ontbreekt er een verband met Giuliano de’ Medici, de geciteerde opdrachtgever van het portret uit het Louvre.

10. Isabella van Aragon:

Dat de dame op het portret uit het Louvre Isabella van Aragon (1470-1524), de echtgenote van Galeazzo Sforza hertog van Milaan, zou zijn is de aparte zienswijze van Maaike Vogt-Luerssen. Het schilderij moet dan echter gemaakt zijn in 1489 toen Isabella 19 jaar was, zodat de hele bestaande datering op de helling komt te staan. De geportretteerde zou rouwkleren dragen wegens het overlijden van haar moeder Ippolita Sforza, maar die was al gestorven in 1484, en waarom zij dan zou glimlachen is hoogst eigenaardig. Op de rand van haar kleed zouden de emblemen van de Sforza & Visconti te herkennen zijn.

Fig. 8 Isabella van Napels of Aragon (Raffaello Sanzio, Galleria Doria Pamfili, Rome)

Nadat zij in 1494 weduwe geworden was zou zij 3 jaar later in het geheim met Leonardo da Vinci getrouwd zijn en nog 2 zonen en 3 dochters met hem gehad hebben (geboren tussen 1498 en 1510).

Er bestaat volgens dezelfde auteur een gelijkenis met andere portretten van Isabella (Lisa) zoals het portret door Rafael in Rome (zie fig.8) en zij zou dan ook afgebeeld staan op een hele reeks andere werken van da Vinci zoals de Madonna van de Rotsen, de Sint-Anna ten Drieën en het Laatste Avondmaal (als Johannes). In dat geval zou het ook Isabella moeten zijn die met de Mona Lisa van Isleworth kan geïdentificeerd worden.

Men zou zich hierbij ook kunnen afvragen waarom kardinaal Luigi van Aragon, die het schilderij gezien had in 1519, zijn nicht Isabella niet zou herkend hebben en waarom Leonardo en zijn vrouw elkaar achteraf in de steek gelaten hebben; zij vertrok naar Bari in 1500 en hij ging in 1516 naar Amboise…

Besluit:

Er zijn dus theorieën genoeg in verband met de identiteit van de Mona Lisa of la Gioconda, waarvan de ene al geloofwaardiger is dan de andere. Het is wachten op nieuwe bevindingen die de exacte waarheid kunnen onthullen en de raadsels omtrent deze mysterieuze dame eindelijk zullen oplossen. Voorlopig is zij echter nog altijd Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo.

JVL

Who is Mona Lisa?

Since 2005, it has generally been assumed that Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (or La Gioconda) can be identified with Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo (see art Leonardo da Vinci, Lisa Gherardini and Francesco del Giocondo). Besides the world-famous Mona Lisa of the Louvre (from 1513-17), there is also the Mona Lisa of Isleworth from 1503, which is considered to be another (earlier) version (see art. The Mona Lisa’s of Isleworth and the Louvre).

Both portraits are original works by the artist, probably assisted by his pupils. After all, it was not uncommon, that several versions of a work were painted, albeit under his supervision and with the master's personal touch.

However, not everyone is convinced that the lady Leonardo has portrayed is Lisa del Giocondo and a lot of theories have been put forward in recent decades, which are sometimes a bit far-fetched, but sometimes also surprising and interesting.

1. An idealized fictional character:

Perhaps Mona Lisa is Leonardo's ideal type of a human figure, his ideal of beauty, which was supposed to be a synthesis of his beloved persons (men and women). Anyone who knows da Vinci's work can see that his Mona Lisa type regularly returns as a female character in a number of other paintings. For example, there is a similarity with the unfinished carton with Saint Anne (National Gallery) from 1498 and the Virgin with Child and Saint Anne (Louvre) from 1510 (see fig.1). The same type of woman may also appear on the Madonna of the Rocks (version Louvre 1483-86 and version National Gallery 1491-1508).

Da Vinci's androgynous figures show both feminine and masculine traits; one thinks of the figure of John the Baptist (see below) and the figure of John the Apostle at his famous Last Supper.

The theory of the idealized fictional character is very plausible because many other artists (such as Sandro Botticelli) were repeatedly painting the same figure. But as with Botticelli, it is not excluded that the character is still based on a real person.

2. Leonardo's mother:

Leonardo was the illegitimate child of notary Ser Piero d'Antonio da Vinci and a certain Caterina Lippi, an orphan girl from the neighborhood who was later married off to a local farmer Antonio Butti. Young Leonardo was taken into the family by his father, when he married Albiera Amadori. It is difficult to assume that the lady depicted would be the woman of low descent that his mother most likely was.

3. Leonardo himself:

Because of the resemblance with a later self-portrait (from the Library of Turin) one could recognize in the figure of Mona Lisa the facial features of Leonardo (see fig.2). It is always possible that the artist (who was homosexual or bisexual ) wanted to externalize his feminine side. This theory is also in line with the idea that the Mona Lisa could be a portrait of his mother.

4. Andrea Salai (Gian Giacomo Caprotti di Oreno):

There is also a very strong resemblance between the Mona Lisa and the figure of Saint John the Baptist (1513-16) from the Louvre which is believed to be his pupil (and lover?) Andrea Salai (see fig.3). Salai entered Leonardo's studio when he was 10 and remained his companion for 30 years.

According to his diary Andrea de Beatis, (the secretary of Cardinal Louis of Aragon, who had visited Leonardo in France in 1517), saw the painting of Saint John together with the portrait of a Florentine lady and the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne in 1517 in Leonardo's home in Clos-Lucé, where Salai lived with him.

For some authors, Salai could even have been the co-author of (one of) the Mona Lisa’s. He is also said to have been the model for the Monna Vanna ("The Vain Woman or the Naked Mona Lisa"), a charcoal sketch made in da Vinci's studio and also preserved in the Louvre. The resemblance to the Mona Lisa is obvious (see fig.4).

This theory ties in with the idealized male-female type. As with Michelangelo's statues in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo, breasts have been added to the male torso (with muscular arms).

To prove that Salai was indeed a model for the Mona Lisa, some "art connoisseurs" have argued that Mona Lisa is an anagram for Mon Salai. However, they forgot that Monna Lisa (short for Madonna Lisa) is actually written with double n.

According to Silvano Vinceti, the letters L (Leonardo) and S (Salai) can be found on Mona Lisa's eyelids, but that seems more like wishful thinking (see below).

5. Pacifica Brandano, Isabella Gualanda of Costanza d’ Avalos:

When Andrea de Beatis spoke of the portrait of a "certain Florentine lady, who was painted in vivo on behalf of the late Giuliano de' Medici", he was (according to some) referring to one of the mistresses of Giuliano (the youngest son of il Magnifico). These ladies should then be Pacifica Bradano, Isabella Gualanda or Costanza d'Avalos. Giuliano is said to have had a portrait made of Pacifica shortly after the birth of their son Ippolito and her death in 1511 (see art. The mysterious death of Ippolito de' Medici).

Giuliano himself died in 1516 before the portrait was completed. So there was no client anymore and perhaps Leonardo repainted the portrait with Mona Lisa as we know her today.

Pacifica came from Urbino, so it is unlikely that she was the Florentine lady. That it would be Isabella Gualanda from Naples, who mentions De Beatis in his diary, but not explicitly as Giuliano's mistress, is very doubtful and that it would be Costanza d'Avalos, the Duchess of Francavilla, whom Giuliano apparently did not even know, is particularly implausible.

It is however not excluded that Giuliano (when Leonardo had entered his service in Rome in 1513) had him painted a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, whom he knew from his youth (see Leonardo da Vinci, Lisa Gherardini and Francesco del Giocondo). So it could have been a painting of a “Florentine lady”, whose identity Leonardo apparently had kept a secret from De Beatis.

6. Fioretta Gorini:

According to Angelo Paratico, the mysterious Florentine lady would have been Fioretta Gorini, the mistress of Giuliano de' Medici, the brother of Lorenzo il Magnifico, who was murdered in April 1478 during the Pazzi attack. So Leonardo was not speaking about the late Giuliano the Duke of Nemours during his conversation with the Cardinal of Aragon and Andrea de Beatis, but about the duke’s deceased uncle of the same name. He would then have commissioned the young Leonardo to paint Fioretta's portrait in 1477/78 when she was pregnant. Shortly after the birth of her son Giulio (later Pope Clement VII), however, she died in that same 1478. With the portrait of Ginevra de' Benci (from the National Gallery) painted around the same time Leonardo had proven that we was capable to make such a work. The painting of Ginevra is also said to be a portrait of Fioretta. Since the client and the sitter were dead, Leonardo kept the painting with him.

The fact that Leonardo used poplar wood for the portrait and only switched to walnut during his Milanese period is not a very strong argument for the dating.

According to this theory and in contrast with the writings of Vasari, the portrait was not painted in 1503, but 25 years earlier. Fioretta was 24 years old at the time, but the lady in the portrait from the Louvre is older. The findings of Pascal Cotte, who discovered an underlying figure of a younger woman on the Mona Lisa’s portrait from the Louvre, would then confirm that it was probably painted earlier. But with whose portrait Fioretta then was overpainted is not clear. Because of the problems with chronology, this theory is not very convincing.

7. Lisa del Giocondo del Giocondo:

Since Vasari nowhere explicitly mentions the name Lisa Gherardini, but only speaks of Lisa del Giocondo, Giuseppe Pallanti argues that the sitter is Francesco del Giocondo’s sister, who was therefore also called del Giocondo and not Gherardini. She was married to her cousin, another Francesco (or Pierfrancesco) del Giocondo and also a silk merchant.

On the one hand there is something to be said for this theory, because in the Renaissance it was customary for women to keep their own family name, but on the other hand this Lisa (born in 1468) would have been 35 years old in 1503 and 49 years old in 1517 and it is therefore unlikely that she was the lady of the portrait . It may be that Vasari did not find it necessary to mention Lisa's maiden name Gherardini .

It certainly is remarkable that Agostino Vespucci (cousin of Amerigo and collaborator of Niccolò Machiavelli) in his note of October 1503 on a work with "Letters of Cicero" from the University Library of Heidelberg (see art. the Mona Lisa’s of Isleworth), mentioned a painting by Leonardo called “Lise del Giocondo” (and not Lise Gherardini…).

8. Cecilia Gallerani and Lucrezia Crivelli:

The portrait of Cecilia Gallerani is also known as the Lady with the Ermine and is preserved in the Museum of Krakow and the portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli from the Louvre (see fig. 5) is also called La Belle Ferronnière. There may be some resemblance to the Mona Lisa, but the ladies are identified as mistresses of Duke Ludovico Sforza and were portrayed by Leonardo during his Milanese period (between 1489 and 1496). La Belle Ferronnière may also be a portrait of Beatrice d'Este, Duke Sforza's wife. The hard-to-recognize letters (B?) S on Mona Lisa's eyelid could, according to prof. Vinceti also refer to this Beatrice Sforza.

9. Caterina Sforza and Isabella d' Este:

Caterina Sforza, countess of Forli, is also said to be the Mona Lisa. But her portrait la dama dei Gelsomini is attributed to Lorenzo di Credi (see fig.6). It dates from 1481/82 and is kept in the Pinacoteca of Forli. If one compares this painting with the Mona Lisa, one has to conclude that it is the image of another woman (see art. Caterina Sforza, the tigress of Forli).

When Leonardo was in Mantova in 1499, marchioness Isabella d' Este asked him to make her portrait. In the Louvre, the preparatory drawing (in profile) has been preserved, which is thought to be by Leonardo and which indeed has similarities with the portrait of Mona Lisa (pose, chin, hands and hair). There are few similarities with later images of Isabella d' Este.

The drawing must then be made 3 to 4 years earlier than the 1st Mona Lisa, which Vasari identifies as Lisa del Giocondo. It is possible that Leonardo would have based Lisa’s portrait on Isabella's sketch (see fig.7). But to identify the Mona Lisa from the Louvre with Isabella, there is lack of a connection with Giuliano de' Medici, the quoted patron of the portrait from the Louvre.

10. Isabella of Aragon:

That the lady in the portrait from the Louvre would be Isabella of Aragon (1470-1524), the wife of Galeazzo Sforza Duke of Milan, is the remarkable theory of Maaike Vogt-Luerssen. In that case the painting must have been made in 1489 when Isabella was 19 years old, so that chronology is fully disturbed. The sitter is wearing mourning clothes because of the death of her mother, but Ippolita Sforza had already died in 1484, and why she would then smile is rather peculiar. In the neckline of her garment the emblems of the Sforza & Visconti can be recognized.

After becoming a widow in 1494, Isabella would have secretly married Leonardo da Vinci 3 years later and had 2 more sons and 3 daughters with him (born between 1498 and 1510).

According to the same author, there is a similarity with other portraits of Isabella (Lisa) such as the portrait by Rafael in Rome (see fig.8). She would then also be the sitter on many other works by da Vinci such as the Madonna of the Rocks and the Virgin with Child and Saint Anne. And consequently, it must also be Isabella who can be identified with the Mona Lisa of Isleworth.

In all this one might wonder why Cardinal Luigi of Aragon, who had seen the painting in 1519, would not have recognized his niece Isabella and why Leonardo and his wife were separated afterwards; she left for Bari in 1500 and he went to Amboise in 1516...

Conclusion:

There are plenty of theories about the identity of the Mona Lisa or la Gioconda, one of which is already more credible than the other. In the meantime one has to wait for new findings that can reveal the exact truth and solve the riddles surrounding this mystery lady. But for now, she is still Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo.

Literatuur:

Bramly, S. Leonardo : the Artist and the Man. Londen, 1994.

Burke, J. Agostino Vespucci’s Marginal Note about Leonardo da Vinci.

in: Leonardo da Vinci Society Newsletter (mei 2008).

Cascone, S. Was the Mona Lisa based on Leonardo’s male lover?

in: Artnet News (April 2016)

Clark, K. Mona Lisa in: The Burlington Magazine (maart 1973).

Cotte, P. Mona Lisa dévoilée. Les vrais visages de la Joconde. Parijs, 2015.

Herford, S. Le Jocond. Neuilly-sur-Seine, 2011.

Isaacson, W. Leonardo da Vinci. De biografie. Houten, 2017.

Kemp, M. Leonardo da Vinci: the marvellous works of nature and man. Oxford, 2000.

Idem & Pallanti ,G. The People and the Painting. Oxford, 2017.

Kraaijvanger, C. Verborgen letters in de ogen van Mona Lisa? In: Scientias (dec.2010).

Pallanti, G. Mona Lisa Revealed. The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model. Milaan, 2006.

Paratico, A. A New Hypothesis on Leonardo's Mona Lisa. Was She Fioretta Gorini? - Gingko Edizioni (2015).

Schwartz, L. The Computer Artists Handbook. New York, 1992.

Van Laerhoven, J. Leonardo & Michelangelo. Kermt, 2017.

zie art. Caterina Sforza, de tijgerin van Forli.

zie art. De glimlach of de grimlach van Mona Lisa.

zie art. De Mona Lisa’s van Isleworth en het Louvre.

zie art. De mysterieuze dood van Ippolito de’ Medici

zie art. Leonardo da Vinci, Lisa Gherardini and Francesco del Giocondo.

Vasari, G. The Lives of the Artists. Aylesbury, 1991.

Venturi, A. Storia dell ‘Arte Italiana. Milaan, 1901.

Vogt-Luerssen, M. Wer ist Mona Lisa? Norderstedt, 2003.

Idem Fioretta Gorini (and not Ginevra de Benci) – kleio.org